Monero’s recent dynamic block-size upgrade will help prevent specific attacks such as the “big bang attack” (i.e., a bloating spam attack to make the blockchain bigger than what the nodes can support).

However, the change in their PoW algorithm represents the third change over the coin’s existence to provide increased ASIC resistance. Yet, previous Monero forks did not have a long-lasting impact in preventing ASIC miners, as ASIC resistance is essentially a perpetual “”

Following the fork, the subsequent drop in miner participation has led to lower hashrates. As lower difficulty implies lower mining costs, it has resulted in higher profitability for GPU/CPU miners.

Nevertheless, companies such as Coinhive have halted their Monero mining services1, citing a decrease in the price of Monero as a key decision factor. Whereas profitability jumped, the increase in absolute mining revenues remain low.

Similar to other proof-of-work blockchains, the Monero community faces a tradeoff between centralization and increasing risks associated with lower mining contributionowing to ASIC resistance.

Over its 5-year existence, XMR developers changed the PoW mechanism of Monero software three times in order to achieve . XMR development team typically has scheduled upgrades twice a year2 for a variety of reasons, such as upgraded security or privacy features. As a result, the protocol has been split into several versions over the years owing to disagreements over these forks.

As an example, in April 2018, following disagreements regarding the community’s proposed changes3, Monero (XMR) was forked onto several alternative chains: Monero Original (XMO), Monero Classic (XMC)4, and Monero 0 (XMZ)5. While these projects all claim to represent , only one of them remains somewhat active, with both development & public interest for XMO and XMZ quickly fading away after release.

1. Monero’s Fork in March 2019

Most recently, Monero (XMR) forked again on March 9th, 2019 but, unlike in April 2018, it was a non-contentious fork that occurred without the creation of any side chain. This time, four justifications were provided for the hard-fork6:

an update in the dynamic block size algorithm designed to prevent a big bang attack7 (also referred to as a “spam bloating attack”).

a change in the PoW algorithm (from CryptoNight V8 to CryptoNight-R) in order .8

the addition of a dummy encrypted payment ID to improve transaction homogeneity. Transaction homogeneity refers to increased fungibility of the cryptoasset, meaning that an individual coin’s history cannot be tainted (like Bitcoin or Litecoin) as addresses are not linked together. In simple terms, Monero is similar to physical bills in the sense that it cannot be traced to the previous owner.. As a result, the value of one Monero is always equal to one Monero.

the simplification of amount commitments through the shrinkage of and the use of .

Previous attempts to discourage ASIC miners did not have a long-lasting impact. However, ASIC resistance is somewhat of a “cat and mouse”9 game with no permanent solution that completely prevents ASIC mining.

Prior to the March 2019 hard fork, Monero was reportedly dominated by ASIC miners10, with ASICs contributing up to 85% of the network’s cumulative hashrate. Thus, the community decided to push a hard fork update that would force all participants to upgrade to the new protocol.

2. Consequences of Monero’s March 2019 fork

2.1. Added privacy features and improved security

Newly-included privacy elements such as the addition of dummy information make it harder to determine both the origins and the destinations of every transaction. As several countries (e.g., France11) and individual US states (e.g., Texas12) are discussing whether or not privacy coins should be banned, this additional privacy feature may lead to higher pressure on countries to create legislature to directly address the status of privacy coins.

Regarding the improvement in the countermeasure to prevent a “big bang attack”, the initial issue was that the size of the block could increase exponentially.

Constraint on block-size calculation: Previously, the only constraint on block sizes was that it couldn’t be higher than the median size of the preceding 100 blocks.

Initial risk: Spam attacks were still possible by maximizing the size of each block in order to increase the potential limit of subsequent block sizes. As the total blockchain size is derived from the sum of all existing blocks, a continuous increase of each individual block could lead to an exponential growth of the entire chain, causing nodes with less available disk space to be disconnected from the network. For an in-depth explanation on “big bang attack”, please visit:https://github.com/noncesense-research-lab/Blockchain_big_bang

Solution: Firstly, XMR development team introduced a long-term (“LT BlockWeight”) median over the previous 100,000 blocks.

Going forward, the long-term blocksize can only increase by up to 1.4x after 50,000 blocks14.

A second addition is the change in the miner fee as it is now calculated based on a long-term median block weight versus the previous 100-block median weight. Before the fork, clients used a multiplier of the minimum fee during periods of high activities to obtain priority for their transactions and a part of the base block reward would be withheld if the blocksize was higher than the median over the previous 100 blocks. As fees are now set based on the long-term median block weight, fees would not decrease when the amount of transactions keep increasing at a lower pace.

2.2 Consequences of the fork

In line with analysis that suggested Monero was mostly mined by ASIC mining equipment15, all of these miners were virtually impacted by the fork. Three sub-consequences were directly observable.

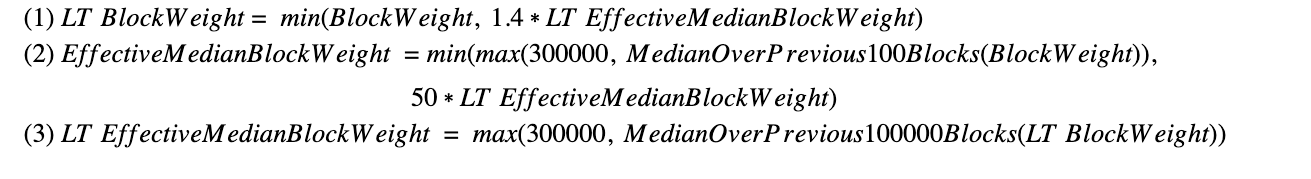

2.2.1 Sudden drop in hash rate

Chart 1 - Monero hash rate (in GHash/s) since January 2017

Between March 8th and March 10th, the hash rate dropped roughly 70%, thereby validating previous pre-fork estimates about the heavy contribution rate of ASICs to Monero’s total network hashrate.

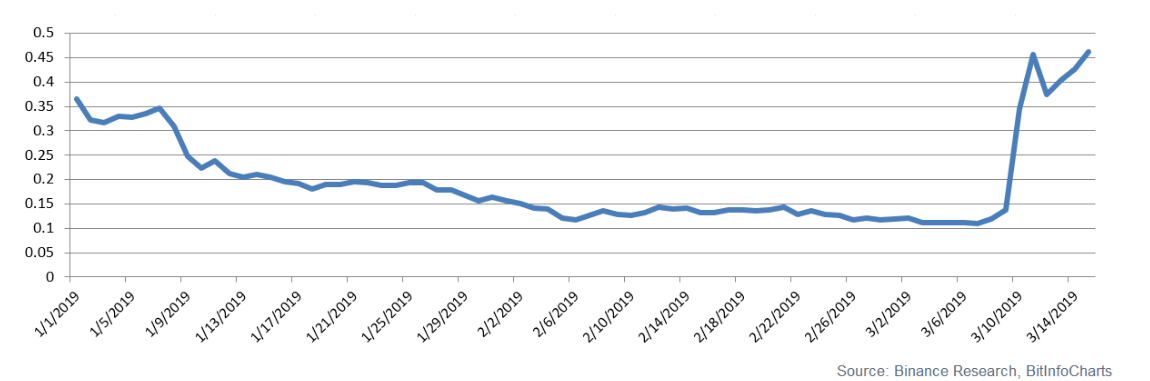

2.2.2 Increasing block profitability

Chart 2 - Mining profitability (USD/day for 1 kH/s) since January 2019

In the aftermath of the fork, as the difficulty of mining a block decreased, the profitability per block increased sharply by over 200%. On average, the network’s mining difficulty decreased by more than -70%, in line with the slump in the hashrate, meaning that the same CPU or GPU card on average could produce nearly 3 times as many Monero post-fork, on average. The cause of this is two-fold:

ASICs are incredibly efficient at mining, so removing their contributions to the network means that the average variable cost of mining on Monero is much higher using general purpose units (GPUs) or alternative hardware used by miners.

Lowering network difficulty also offers a more even playing field for smaller miners using household machines. After past forks and their corresponding jumps in mining profitability, Moore’s law (chart 3) has been observed, with profitability decaying gradually over time until the next fork was introduced. This time around, it remains to be seen if the same eventual decay in mining profitability will occur once more.

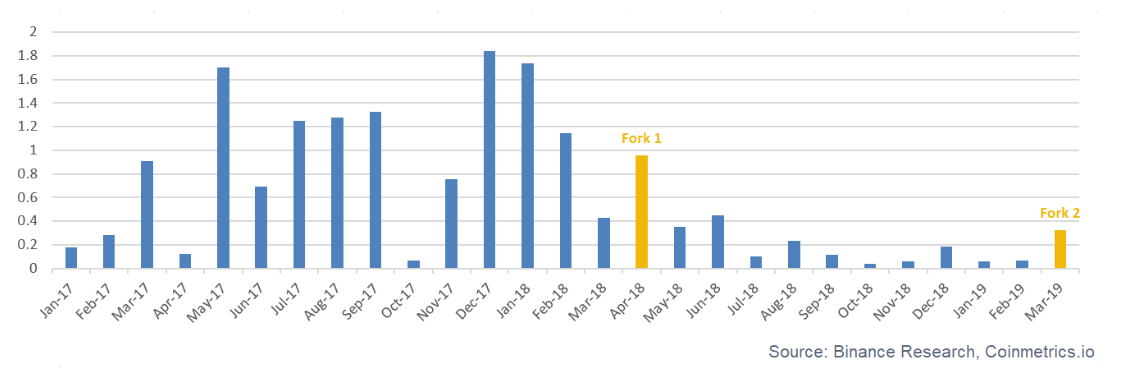

Chart 3 - Mining profitability (USD/day for 1 kH/s) since January 2017

2.3.3 A brief spike in blocktime

Chart 4 - Monero average blocktime (in minutes) since January 2017

Shortly after the upgrade, the block-time spiked from an average of 2 minutes to more than 10 minutes on March 10th. Though ASIC miners were excluded from mining activities instantaneously after the fork and the overall network hashrate decreased, the mining difficulty was mathematically designed to not adjust instantly.

As a consequence, fewer miners were competing for blocks with pre-fork difficulty levels that assumed higher network aggregate hashrates, leading to longer block times.

Interestingly, with longer block times, any adjustments that are implemented at future block height mean that adjustment time is pushed back in terms of real time, further exacerbating the duration of these symptoms. It took roughly 36 hours for the average block-time to return to the normal average of two minutes per block. Unsurprisingly, the fork from April 2018 also led to a similar scenario (as illustrated by the first spike in the chart above to just under 10 minutes per block).

3. Conclusion: the fork’s outcomes

Outcome 1: Mining remains fairly unprofitable for household miners

Even though the difficulty has dropped by ~75% since the fork, the profitability increased greatly but the month-on-month increase in absolute USD terms is fairly low.

Chart 5 - absolute MoM change in mining profitability (USD/day for 1 kH/s)

As a result, it hints that the project’s efforts to involve more individual users in the network may not be so effective (“fork 2”) with this fork boosting mining profitability by only one-third of the absolute change in the aftermath of the previous fork (“fork 1”).

As 20-25% of the size of the pre-fork mining power remains, it suggests that some of the miners still expect a strong price rebound or that they benefit from lower marginal costs for mining than empirically suggested. In comparison, the April 2018 fork (“Fork 1”) had a larger impact in mining profitability, as the price of Monero was more than 3 times higher than XMR price in March 2019, resulting in a much wider magnitude in USD-denominated mining profitability in the aftermath of the two forks.

Outcome 2: Low hashrate = higher probability of 51% attack

As ASIC miners were forced to “opt out”, the hashrate dropped by more than -70%, resulting in a slightly higher risk of a 51% attack.

In general, ASIC miners may lead to centralization of the mining activities behind any PoW asset, but their absence also exposes a greater tail risk for the network.

Achieving “ASIC resistance” remains a cat and mouse game and there is a trade-off between staving off centralization and boosting mining participation rate. Perhaps an alternative solution would be to encourage competition, transparency, and even collaboration in the ASIC mining industry, such that communities can be in more control in the operations of their networks.

Forks - whether hard, soft, contentious, or non-contentious - are normal events in the crypto-industry and frequent forks may indicate healthy development behind a crypto network. Regardless of the outcomes from this fork, the XMR development team continues future improvement of Monero, with the next fork being already scheduled for October 2019.